Olympics Interview

In 2020, the global pandemic postponed the Tokyo Olympics, dashing the hopes of athletes who had been training for years for a chance to compete with other athletes from around the world. This year, the Olympic Games are on track for competition without public spectators, but the pandemic could still derail those plans. How does this disappointment and uncertainty affect an Olympic athlete? How do athletes prepare for the Olympics? Two Otterbein faculty members have answers to those questions and more.

Associate Professor Bruce Mandeville

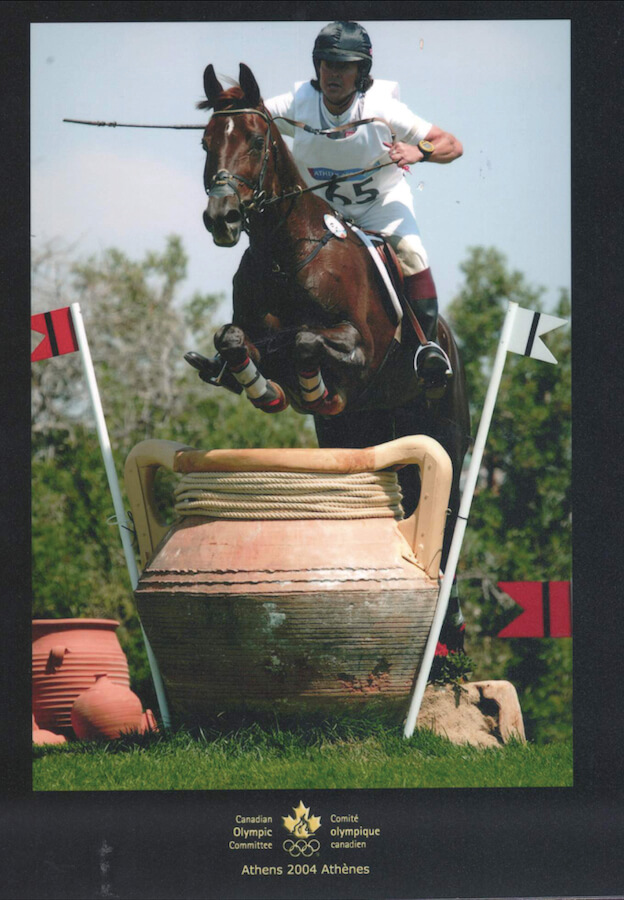

Associate Professor Bruce Mandeville competed in the 2000 Sydney and 2004 Athens Olympic Games, two World Championships (1994 and 2002), and two Pan American Games (1999 and 2003) as a member of the Canadian Equestrian Team. He is an accomplished coach and dressage horse trainer. He has coached students in the North American Young Riders Championship (NAYRC) to a gold and bronze medal. At Otterbein, he teaches equine business management courses, including sustainable practices, equine center design, and equine law, among others.

Associate Professor Bruce Mandeville competed in the 2000 Sydney and 2004 Athens Olympic Games, two World Championships (1994 and 2002), and two Pan American Games (1999 and 2003) as a member of the Canadian Equestrian Team. He is an accomplished coach and dressage horse trainer. He has coached students in the North American Young Riders Championship (NAYRC) to a gold and bronze medal. At Otterbein, he teaches equine business management courses, including sustainable practices, equine center design, and equine law, among others.

Q: As an athlete, what does it take to prepare mentally and physically for Olympic competition?

Mandeville: For major competitions, athletes (and the horses) try to peak at the right time, not too early or late. Physical peak is easier to monitor and attain than mental peak. Having delays of even hours or days can influence a competitor’s mental state. Having months of uncertainly would be disarming. With two team members (rider and horse), there are many more physical and mental variables to consider. Preparation takes a village, including sports psychologists, which are often part of the traveling team.

Physically, national team members, during my years, were given physical therapy sessions to help with pains and strains. I also had a sports masseuse and osteopathist attend major competitions. Outside of competitions, my horse often got more medical attention than I did (those approaches and techniques I use today in my equine therapies classes).

Q: What should people know about the experience of competing in the Olympics?

Mandeville: The Olympics offers a unique atmosphere. The Olympic Village is often not accessible to all sports due to the various venue locations. Equestrians need land, so we rarely get to be in the village. The different countries identified by sportswear in the restaurants and gyms is memorable and exhilarating. Often, lifetime friends are made.

The Olympics also represent extreme stress — mental and physical, not only on the athlete but his/her support group. Finding a life partner or friends who understand the commitment and sacrifices poses a huge hurdle. Another stress is that just one thing could go wrong: a horse misstep in training, for example, and *poof* — that opportunity is gone.

Life after the Olympics can be tough. Athletes often suffer mentally and physically, including gaining

weight from not being on the same workout regime after retiring from the sport. The bright side is that the Olympics undoubtedly change athletes’ lives, and opens doors, opportunities, and new experiences.

Q: How has the pandemic changed Olympic qualification?

Mandeville: The postponement will affect athletes differently. Some will be advantaged, others not. Equestrians work in four-year cycles: World Championships, Pan American Games, then Olympics, followed by a year off. A certificate of capability is required to compete. For individual riders (not the team qualification), those required results last for 12 months. Team results from the Pan Ams and Worlds will qualify a country to send a team. Having a postponement creates chaos in this system, which is designed to keep riders safe.

The major competitions where one qualifies are “on again, off again” due to changing COVID circumstances; canceled competitions limit where equestrians can get qualified for the Olympics. On the bright side, riding horses is pretty COVID friendly — open riding areas (even indoors) offer plenty of airflow, and horses require social distancing (standing too close can get you kicked). COVID challenges many aspects of life, but equestrians benefit from still being able to ride during the pandemic.

Senior Instructor Denise Shively

Senior Instructor Denise Shively teaches public relations and health communication courses in the Department of Communication, as well as First Year Experience, Integrative Studies and Senior Year Experience courses. When she isn’t teaching, she is involved in artistic swimming, formerly known as synchronized swimming. She is the current president of USA Artistic Swimming and has been working closely with the national team that is hoping to qualify for the Olympic Games. In previous roles as vice president of the U.S. Synchronized Swimming board of directors and as an international team manager, she traveled with Team USA to many World Championships, three Pan American Games, and the 2008 Olympic Games.

Senior Instructor Denise Shively teaches public relations and health communication courses in the Department of Communication, as well as First Year Experience, Integrative Studies and Senior Year Experience courses. When she isn’t teaching, she is involved in artistic swimming, formerly known as synchronized swimming. She is the current president of USA Artistic Swimming and has been working closely with the national team that is hoping to qualify for the Olympic Games. In previous roles as vice president of the U.S. Synchronized Swimming board of directors and as an international team manager, she traveled with Team USA to many World Championships, three Pan American Games, and the 2008 Olympic Games.

Q: How long have you been working with artistic swimming champions?

Shively: I was asked in 2003 to serve as a team manager for our junior national team. Following the Junior World Championships in 2004, I “moved up” with the coaches and some of the team members to the senior level. Those are the athletes who ended up training for the 2008 Olympic Games. As a national team manager, I handled logistics for and represented the team officially at international competitions. That meant I was booking flights and ground transportation, securing hotel rooms, helping on deck during training, and supporting the team in any way that was non-coaching. Now as president of USA Artistic Swimming, I chair the board of directors and work to bring visibility and support to our members and the sport.

Q: What does it take to manage athletes at the Olympics?

Shively: As the manager at an international competition, I work with the coaches to figure out what time to walk to the bus, attend very tightly timed practice sessions in the pool, watch film of practice, get back on the bus, eat, recover, and repeat the next day. Schedules are prepared to the minute for each day. There’s no free time. People may not realize how many volunteers it takes to run such an event. That’s my favorite part of traveling internationally with the team. Often the volunteers are young adults or college students who want to practice their English. I have gotten to know so many young people from so many countries as a result of this experience and have kept in touch with many of them.

Q: How has the pandemic changed the way these athletes are preparing?

Shively: Our athletes were some of the leaders to embrace virtual training, especially land training. They organized sessions and invited athletes from around the world to join them. They were especially effective in building a supportive community of artistic swimmers whose training plans suddenly had to adapt. They worked with the international body FINA to host international land competitions. In February, the USA hosted a virtual World Series competition, the first of its kind.

Since the athletes are based in California, they had to follow state guidelines about returning to the pool and had to remain “in their bubble.” They often could not see family members or friends during holidays or other times of year to remain safe, healthy, and to be in compliance. Although that has been challenging, this group has remained focused on their goal of qualifying for the Olympic Games.