Black History Month: Otterbein and Sierra Leone

Posted Feb 10, 2026

February 1856. Otterbein sends its first missionaries to Sierra Leone. Despite a disastrous first trip, the seeds were planted for a long relationship that has spanned over 150 years and counting.

The population of Sierra Leone boasts a vast system of roots. Great Britain created a colony at Sierra Leone as a home for Africans from many different nations who had fought for England during the American Revolution and later for former slaves who were freed when Britain abolished slavery. The new residents set up a naval port at Freeport to intercept slave ships. Many of those rescued slaves would also settle in Sierra Leone.

The United Methodist Church in Sierra Leone today traces its history to 1855, when the Church of the United Brethren in Christ began mission work there.

A leading institution within the church at that time, Otterbein’s missionaries soon followed in February 1856. Rev. William Shuey, Rev. D.R. Kumler, and Rev. J.K. Flickinger lasted only a few months in Sierra Leone before falling ill to native diseases and returning home. But three years later, more missionaries set out to continue building the relationship with the West African country.

A student named C.O. Wilson joined the mission work there in 1860, and in 1862, the first woman missionary to travel to Sierra Leone from Otterbein was Amanda Hanby, sister of Benjamin Hanby.

Tribal revolts over hut taxes claimed the lives of seven missionaries in 1898, and the church considered withdrawing from Sierra Leone but decided to stay. Otterbein missionaries after the tragedy included Lloyd Mignerey, class of 1917, who served in 1922, and Glen Rosselot, class of 1916, who served from 1927-1939.

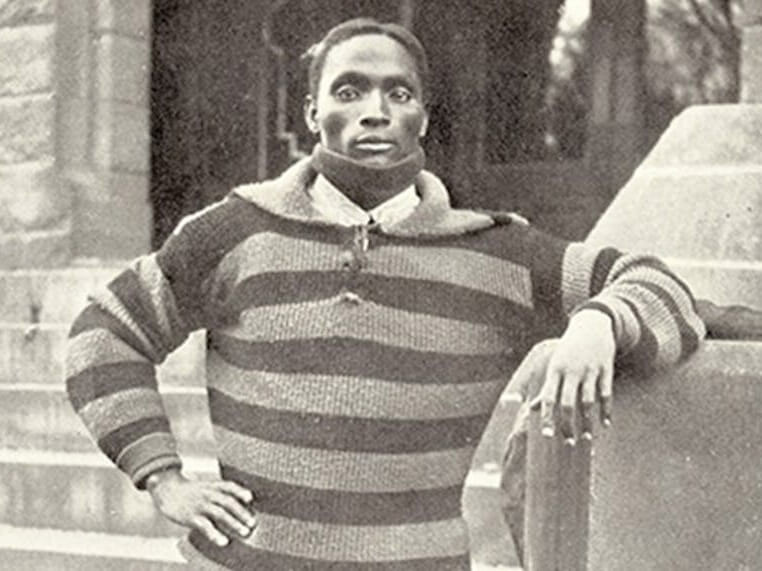

Lucy Caulker, the daughter of a tribal king, was one of the first converts, and many of her direct descendants made their way to Otterbein. The first was Joseph Hannibal Caulker, a prince of the Bolun tribe in Sierra Leone who was educated by United Brethren missionaries enrolled at Otterbein in 1896.

The notebooks Caulker kept while in the United States give a unique look into what it was like for a West African to walk the streets of New York City, as well as those of Westerville. He was amazed by the tall buildings, trolley cars, and the streets filled with people of all different races. At Otterbein in the springtime, Caulker enjoyed the chirping robins, the native plants and the shade trees, but in winter, he longed for “that sultry land where the sun lavishes his energy and the palm tree everywhere majestically waves its evergreen branches under the azure canopy.”

While the local weather was not always to the liking of Caulker, the religious spirit of Otterbein was. A pious Christian, Caulker admired the dedication and enthusiasm of both students and professors. The bright and friendly Caulker was popular within the Otterbein community, which was devastated by tragedy when, on Dec. 6, 1900, Caulker was burned to death in an explosion caused by a small oil stove in his room.

Other descendants of Lucy Caulker who attended Otterbein include Richard Kelfa-Caulker ’35, who became ambassador to the United States and later the United Nations from Sierra Leone; and John Karefa-Smart ’40, who became minister of external affairs for the independent government in 1961.

Through the years, many other Otterbein graduates from Sierra Leone forged successful careers on both the national and international stages. Sylvester M. Broderick, class of 1924, served as director of education in Sierra Leone; Amelia Caulker Ben-Davis ’59 was a member of Sierra Leone’s parliament; Victor Sumner ’59 became a diplomat in London; Miatta Akiatu ’65 worked for UNESCO in Paris; and Emma Broderick ’67 was affiliated with both the Economic Community of West African States and the Sierra Leone Bureau of Tourism and Culture.

Another successful Otterbein graduate from Sierra Leone was John J. Akar ’51, who became head of the national radio broadcasting service in Sierra Leone and composed the nation’s national anthem. In 1961, Sierra Leone became an independent nation, free of British rule and was named the 100th member of the United Nations. On the day the country was granted independence, April 27, 1961, Akar aired a version of the national anthem as sung by the Otterbein men’s glee club.

He also was a leader in the arts in Sierra Leone, and had previously acted onstage with Richard Burton and Sidney Poitier.

Sylvester Modupe Broderick Jr. ’63, son of Sylvester Modupe Broderick ’24, and Imodale Caulker-Burnett ’63, daughter of Richard Kelfa-Caulker ’35, were the first graduates after Sierra Leone gained independence.

Caulker-Burnett chose to come to Otterbein after generations of family came before her. Her experience at Otterbein is a far cry from what she would experience today. “My first memory was my arrival at an all-White school where there were only six Black students! Four of us were Africans,” she said.

“I joined the Women’s Glee Club, pledged Theta Nu sorority and made some very good friends,” said Caulker-Burnett. “In my sophomore year, I had a roommate with whom I roomed for the remainder of my stay at Otterbein. We became fast friends.”

Life for Caulker-Burnett wasn’t without challenges, however. While she toured Ohio with the Glee Club, she couldn’t tour Florida with them because the state was still segregated.

Caulker-Burnett had a prestigious career in nursing in the United States, and established development and health services in her ancestral village of Mambo, Sierra Leone, and traveled there frequently.

In 1968, Otterbein College began a program to send student teachers to Sierra Leone through a study abroad initiative. Fifteen students spent 10 weeks during the winter term of 1969-1970 in Sierra Leone, working in the schools and studying the culture of the country.

Working alongside Peace Corps and other volunteers in a small inland city, they often worked in open-air classrooms with students who were eager to learn. In Sierra Leone, families paid for children to go to elementary and high school, then if they passed a test, college was free.

Due to the close relationship with Sierra Leone, the nation plays a heavy influence and Otterbein’s art collection. Many of the missionaries to West Africa took a special interest in the art of the region and returned to the United States with African art and artifacts, bestowing the Otterbein art collection with decorative jewelry, masks, sculptures, baskets and weavings, and handicrafts.

The collection became Otterbein’s official African Art Collection in 1969 with a grant from the Kress Foundation. Art Chair Earl Hassenpflug began touring North and West Africa in 1969 to collect new items for the collection, which have been displayed in Otterbein’s galleries over the years, including recent years.

You can read more about Otterbein’s connection to Sierra Leone in the December 2009 issue of Towers magazine.